There’s more than one way to grow a tomato in Laramie County

Published in the Wyoming Tribune Eagle Nov. 18, 2022.

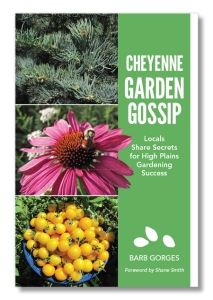

By Barb Gorges

Tomatoes are the epitome of backyard vegetable growing. They test both your gardening know-how and your ability to adapt to your circumstances.

This past summer, two of Laramie County Master Gardeners’ informal garden tours, open to members, friends and family, featured tomatoes, but grown in radically different ways. However, both gardens were located west of town at substantially higher (read “colder”) elevations than Cheyenne.

The first garden, off Happy Jack Road about halfway to Curt Gowdy State Park, is the playground of Ron Morgan. His solution to cold growing conditions 500 feet higher than Cheyenne is to use a greenhouse.

With plenty of experience in the construction trade, Ron built a sturdy wooden frame covered in plastic sheeting used for high tunnels and other less-than-permanent structures. Wind and hail made short work of the sheeting, so he installed rigid plastic, 6 millimeter twinwall, which has survived the hail so far.

Ron is also an able internet researcher, and found a clever irrigation system he could build out of used kitty litter buckets and new rain gutters, based on Larry Hall’s “Gutter Grow System.”

Each tomato plant gets its own 5-gallon bucket. A hole is cut out of the bottom and a small basket-like device fits in it, extending below. The buckets sit side by side on top of the rain gutter, with the soil in the little baskets catching the water that fills the gutter, watering the buckets by osmosis. A float determines when more water is automatically added to the gutter.

Ron has 104 buckets on one system, 23 on a shorter system, and is currently growing a few other kinds of vegetables besides tomatoes. You can see how once it is set up it saves time and water.

Ron also uses an economical support system for his vining tomatoes, training them to grow upward by way of strings attached to the ceiling. Little plastic clips clip onto the string and hold the stems. He adds more clips for each stem as it grows. But he also pinches off any secondary stems, or suckers, to concentrate all the energy into the primary stem.

Ron said his favorite tomato for flavor is a cherry-type called “Sweet Millions.” It forms grape-like clusters. His favorite mid-sized tomatoes are “Tasty Beef” and “Big Beef.”

He starts his vegetables in his shop under lights. Though he could transplant them to the greenhouse in April, Ron’s found the required heating isn’t cost effective. He waits until the first or second week in May to plant them – still a couple weeks earlier than in an unprotected garden. By mid-summer he uses shade cloth to keep his plants from getting sunburned.

Charlie Pannebaker, on the other hand, lets his tomatoes sprawl on the ground, uncovered. This summer he trialed 10 varieties to see which would be the earliest, tastiest, most productive in his growing conditions.

None of the visiting gardeners had ever seen tomatoes grown without a support of any kind, but I had, at the Rodale Institute near Emmaus, Pennsylvania. I asked Charlie if it was a Pennsylvania thing. It might be, as it turns out he grew up on a Pennsylvania farm, and this was the way farmers grew tomatoes.

Charlie and his wife moved to their place off Horse Creek Road a couple years ago, after 30 years in southeast Colorado. He knew his new place at 6900 feet elevation, 800 feet higher than Cheyenne, would require short-season vegetable varieties.

When we visited September 8, jumbles of tomatoes in tangles of vines lay on top of black plastic in rows along the drip irrigation lines.

A month later, after unusually late killing frost, Charlie sent me his results.

Of the total 507 pounds from all 10 varieties, the top four producers made up 70%, or 337 pounds. They were, beginning with the most productive, Fireworks, Siletz, Bush Early Girl Hybrid and Summer Girl.

However, he and his wife, Fran, liked the taste of Ru Bee Dawn best and he liked Summer Girl for shape, size and uniformity. Fireworks had the best fruit quality – Early Girl had a lot of blossom end rot.

Fourth of July had fruit ripening two weeks earlier than the others. It had the best yield through August, until the higher yield varieties passed it in September and October (unusually late for killing frost this year).

Next year Charlie is planting Fireworks for yield, Fourth of July for earliness, Ru Bee Dawn for taste and Summer Girl for fruit quality.

He hopes to find new varieties that combine all four attributes, as well as look for an early paste variety.

And Charlie should think about getting some hail protection in case there’s no drought to dry up the hail next year.