Published Nov. 14, 2020 in the Wyoming Tribune Eagle

By Barb Gorges

“You are what you eat,” is a phrase first attributed to a Frenchman in 1826, then a German in 1863. In 1942 it was the title of a book by American Victor Lindlahr. Plants are what they eat, too.

A multitude of sources today tell us we are healthier eating less fat, sugar, and salt. We are also healthier without the chemicals of conventional farming and food processing, as are farmworkers and ecosystems. The enormous growth of the organic food industry in the last decade shows consumers are listening. Even Cheyenne has an all-organic grocery store now.

Back in the 1970s, the organic food co-op I shopped off-campus expected me to bring my own containers and measure out my selections. Today, organic food may come in bulk quantities, but it is often packaged for convenience, even as frozen dinners.

Organic convenience food costs more than what people may be willing to pay to switch to organic. But there are three ways to make eating organic more affordable.

1) Buy basics

And buy a freezer or take up canning if you buy in bulk. But even if you don’t do food preservation, buying already frozen produce is fine. Simple protein-vegetable-fruit meals from scratch don’t take that long to cook if you plan a bit (observes the woman who lets her husband do much of the cooking).

2) Plan for leftovers

Get them in the fridge or freezer asap so they don’t become part of the 40 percent of food thrown out in this country. Soup I make from last night’s leftovers is my favorite lunch and dinner is often creative casseroles.

Cooking mostly from scratch and not wasting food goes a long way to making organic food affordable.

3) Grow your own food.

But not all home-grown produce is created equal.

Your tomato is what it eats—the nutrition it gets from the soil. To get nutritious soil, skip conventional farming and gardening methods, and conventional commercial fruit and vegetable varieties.

Donald Davis, University of Texas at Austin, was the lead on a 2004 study titled, “Changes in USDA Food Composition Data for 43 Garden Crops, 1950 to 1999.” It reported that many nutritional elements are lower in today’s varieties because they have been developed to grow fast.

“Uptake of nutrients has not kept pace with their rapid growth,” Davis said.

Other studies also show a drop in nutrient values over the decades is due to fewer nutrients available in the soil. The more synthetic fertilizers and pesticides are poured on, the less nutritious the soil becomes because beneficial microbes are starved or killed.

And the more you need to keep pouring on. The for-profit chemical companies have had great marketing campaigns since the 1940s to make you think theirs is the only way to grow.

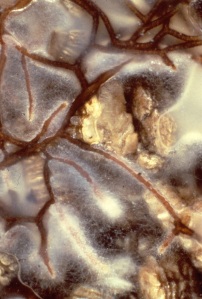

The alternative is to encourage soil microbes to grow in your garden. What do they eat? Compost and mulch, plant and animal materials. And then they feed your plants. See my column, https://cheyennegardengossip.wordpress.com/2017/05/07/soil-microbes-better-than-rototilling/.

J. I. Rodale was one of the early proponents of organic growing, and even the inventor of the term, “organic” to refer to the method. He started the magazine, “Organic Farming and Gardening” in 1942.

Now the Rodale Institute is focused on regenerative organic agriculture. Not just sustainable agriculture but methods that improve ag land. It includes techniques such as permaculture, agroforestry and no-till farming. And organic gardening.

My favorite find at a used bookstore is any book by a garden writer pre-World War II, or even WWI, to find out how they gardened before the age of pesticides and synthetic fertilizers.

Most are not how-to books, however one written in 1961 by Connecticut gardener Ruth Stout is: “Gardening Without Work: For the Aging, the Busy & the Indolent.” The cartoon-like cover also says, “no plowing, no hoeing, no cultivating, no weeding, no watering, no spraying.” That describes organic.

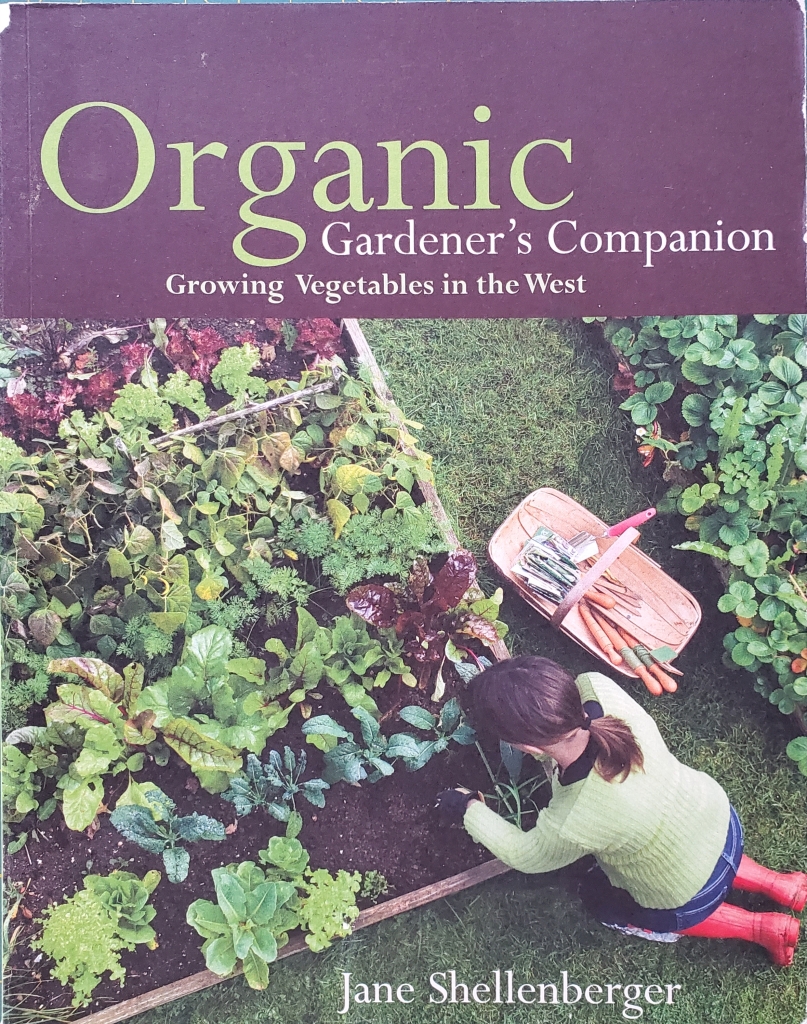

A more available book better suited for us is Jane Shellenberger’s “Organic Gardener’s Companion: Growing Vegetables in the West,” published in 2012. She is the publisher and editor of “Colorado Gardener” magazine. Read all issues free online at https://www.coloradogardener.com/.

See my past columns for how to start your new vegetable garden and smother the grass over the winter where you want it to be. Also, Google “organic vegetable seed companies.” You deserve to eat well and be well.

The Boys and Girls Club of Cheyenne gave permission to take and post these photos with this story. Red wiggler photo by Barb Gorges.

The Boys and Girls Club of Cheyenne gave permission to take and post these photos with this story. Red wiggler photo by Barb Gorges.