This perennial garden keeps expanding. The raised bed with the hail guard on top is where we grow the vegetables, the sunniest spot in front or back yard. Photo by Barb Gorges.

Published in the Wyoming Tribune Eagle Mar. 5, 2018.

By Barb Gorges

Is this the year you’ve decided you’ll spend more time on flowers and vegetables and make that boring expanse of lawn more colorful and edible? Here’s how to start.

Find the sun

Find where the sun shines on your yard and where the shadows are. This is the very first and most important step you must take. If you didn’t notice last year, you can estimate.

See where the shadows of currently leafless trees fall during the day. Find the sunny, south-facing side of your house.

For vegetables you want the sunniest location possible, at least 6 hours of full, summer sun. Do you have overgrown or dying trees and shrubs that need pruning or removal? However, a little shade by late afternoon keeps veggie leaves from temporarily wilting.

Keep vegetable gardens close to the house so it is easier to step out and pull the occasional weed and pick the ripe tomatoes.

Flowers aren’t as picky about sun because there are kinds suited to different light levels: sun, part sun, part shade and full shade. If you desire to grow a certain kind, google its light requirements.

Block the wind

In most residential neighborhoods there are enough obstacles, houses and landscaping, to blunt the wind. But if you are out on the prairie, you might want to put delicate plants in the lee of the barn or plant a windbreak first.

Get the dirt

Soil is anything a plant can stick a root into.

Good soil for vegetables (and other annuals) has lots of microorganisms that help feed the roots. Most vegetables are big feeders. They use lots of nutrients, so you’ll want to dig in compost the first year and then add layers of leaf/plant/kitchen compost mulch after that as needed. No need to dig again in future years.

If you use chemical fertilizer instead (unfortunately limiting good soil microbes), remember to follow the directions. Too much nitrogen gives you leaves and no fruit and too much of any fertilizer gives you sick or dead plants. And remember, Cheyenne has alkaline soils so do not add alkaline amendments like lime and wood ash.

Perennial plants rated for our zone 5 or colder (Zones 3 and 4), especially native plants, are really quite happy with whatever soil is available. If you are trying to grow flowers in the equivalent of pottery clay, gravel pit or sandbox, you might look for native species adapted to those kinds of soil. Or consider growing your plants in a raised bed or container you can fill with better soil.

Water carefully

Here in the West, water is a precious commodity so save money by not throwing it everywhere. If you have a sprinkler system, make sure it isn’t watering pavement.

The new era of home landscaping encourages us to replace our lawns with native perennials because they use less water. Native plants also provide food for birds, bees and butterflies, and habitat for beneficial insects. The Cheyenne Board of Public Utilities is installing a demonstration garden at its headquarters this spring.

But you will need to water a new perennial garden regularly until it gets established, and at other times, so figure out how far you want to lug the hose or stretch a drip irrigation system.

Once established, a native perennial garden not only takes less water than a lawn, but it doesn’t require the purchase of fertilizers, pesticides or gasoline for the mower. Your time can be spent admiring flowers instead of mowing. Although if you convert a large lawn to a meadow, you may want to mow it once a year.

Vegetables are water hogs. The fruits we harvest, especially tomatoes and cucumbers, are mostly water. Unless you like to contemplate life while watering by hand, check out drip irrigation. You can even put a timer on the system.

Sprinklers, on the other hand, waste a lot of water, especially when it evaporates in the heat and wind before it can get to the plants. If you abstain from watering between 9 a.m. and 5 p.m., you’ll lose less to evaporation.

It cost me $3000 to have the turf dug up for this garden…and the broken sewer pipe replaced. Photo by Barb Gorges.

Deleting lawn

While you can rent a rototiller to open up an area for planting, I prefer to use a sharp spade. I dig one clump of grass at a time, only about 8-10 inches deep, break and shake off as much soil as possible and put the remaining chunk in the compost bin—or fill in a hole in the remaining lawn.

It’s slow going, but I disturb fewer tree and shrub roots that underlay my entire yard. When I get tired of digging, that means I’ve reached the amount of new garden I have the energy to plant this year. I don’t want gardening to become a chore!

The plants and details

In the six years I’ve been interviewing local gardeners and writing monthly columns, I’ve accumulated a lot of information, from seed starting to native grass lawn alternatives to growing giant pumpkins and native perennials. Go to my website, https://cheyennegardengossip.wordpress.com, and on the right side of the page use the search function or scroll through the list of topics.

If you are using your phone, select “About” from the menu and find the search function and topics at the very bottom of the page.

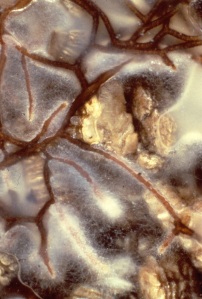

I love this kind of garden visitor. Photo by Barb Gorges.