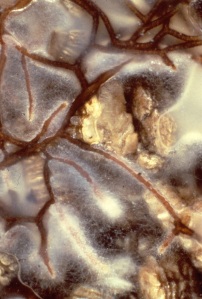

Overall, daffodils are hardier than the average tulip. They are more likely to resist hungry wildlife, snow and drought, and return every year. Daffodils come in a variety of shapes, sizes, bloom times and shades of yellow and orange. Photos by Barb Gorges.

May garden notes: tulip failure, ruthless gardening, bare root planting and mulching everything

Published May 7, 2022, in the Wyoming Tribune Eagle.

By Barb Gorges

You know the ditty, “April showers bring May flowers.”

There is truth to it—if you didn’t water your tulips during our dry April (or last summer), your tulip buds three or four weeks later may be small or not open at all. Quite a contrast from last year. The daffodils and small bulbs don’t seem to be affected as much, but the earliest ones were zapped by that cold snap. The best defense is a variety of bulbs slated to bloom at a variety of times March through June.

My perennial flower beds are mulched every fall by falling tree leaves. The flowers’ stems keep them from blowing away. Underneath, it usually stays moist. In April I start removing layers to expose the early flowering crocus. I start clipping stems, chopping them in small pieces to add to the remaining mulch. But there are a couple areas that blow out and I can never keep mulch in place. This spring I noticed the bare areas have mysterious half-inch diameter holes in the ground. I think they might be ground-nesting bees overwintering. So bare ground isn’t such a bad thing.

Neither is the broken top on the neighbor’s spruce tree, where the Swainson’s hawks have their nest again this year. Neither is the rotten section of another neighbor’s tree where the red-breasted nuthatches are thinking about nesting. Neither are the stringy dead leaves still in my garden that the robins are pulling for nesting material.

There is a time for ruthless gardening. I was reminded by Shane Smith, the Cheyenne Botanic Gardens’ founding director. He was featured in a webinar series last month hosted by the American Horticultural Society titled, “Conversations with Great American Gardeners.” I’d heard him say it before. Do you really want to spend hours hunting scale on a houseplant week after week? Instead, disinfect a cutting and toss the rest of it, which I did, or replace it with something new from the nursery. Isolate the new plant until you are sure it isn’t infected.

I couldn’t resist the exotic tomatoes in the Baker Creek Heirloom Seeds catalog but at least I chose short season ones. So, our bathtub nursery has Berkeley Tie Dye Pink and Thorburn’s Terra-Cotta in addition to my husband Mark’s Anna Maria’s Heart. The extras will be available at the Laramie County Master Gardener plant sale, May 14, 9 a.m., at Archer.

I’ve found homes for amaryllis I’ve started from seed. It takes as many as four or five years until they bloom. Friends are reporting back and some have hybrids of the two I have, a pink and white and a red. However, a lot of the newer varieties of amaryllis have been bred to be sterile, so no hybridizing fun with them. But they can bloom again. No need for dormancy if you don’t mind them blooming naturally sometime between January and April instead of Christmas.

Bare root planting. It’s good for trees, shrubs, tomatoes, flowers, everything. When trees and shrubs are sold in pots or “balled and burlapped,” remove all the packing material, wire, twine and dirt. Spread the roots out in a shallow hole that is wider than it is deep. Don’t add anything but the dirt you dug out. You want those roots to spread beyond the hole instead of becoming dependent on potting soil and fertilizer, circling around and around and the tree being at risk of blowing over a few years later (search “plant a tree” at https://cheyennegardengossip.wordpress.com/).

Bare root also works for flowers and vegetables. But you may amend the soil with plenty of compost for vegetables—they are hungry. For perennial flowers, especially natives, match the kind of plant with the type of soil you have and leave it unamended.

It is better to mulch than to hoe. Make sure the mulch, whether wood chip, straw or other plant material, is not up against the tree trunk or tomato stem, and not too deep—water needs to get through. But you want to shade out the weeds. Most weed seeds require light to germinate. That’s why disturbing the soil with a hoe gives you an unending chore. Try pulling tiny weeds, which won’t disturb the soil much, and cutting off the big ones at ground level frequently.

Finally, my new growing season resolution is to garden in smaller increments of time. Maybe an hour a day removing excess leaves and chopping up last year’s stems instead of a marathon day and a week of sore back. Besides, in spring the yard—and the park and the prairie—are changing quickly and worth frequent walk-throughs.

Published Aug. 13, 2017, in the Wyoming Tribune Eagle, “Covers of Color, ground covers good for replacing grass or gravel, and feeding bees”

Published Aug. 13, 2017, in the Wyoming Tribune Eagle, “Covers of Color, ground covers good for replacing grass or gravel, and feeding bees”