“Great garden books to read in January” was published Jan. 12, 2020, in the Wyoming Tribune Eagle

“Great garden books to read in January” was published Jan. 12, 2020, in the Wyoming Tribune Eagle

By Barb Gorges

January is the traditional time gardeners read seed catalogs. There’s nothing to do outside but maybe prune a few dormant shrubs and trees. It’s also my favorite time to read garden books, old and new.

New “Home Grown Gardening” series

Last year, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt started sending me volumes from their new series, “Home Grown Gardening” and I’m finally getting around to reading them. So far, the series has four installments. They are mostly derived from books published around 1999, several from the Taylor’s Weekend Guide series.

All the books feature detailed introductions and pages and pages of lush new photos, on average one plant per page.

“Container and Fragrant Gardens” is derived from two previous works by Peter Loewer, a prolific garden author in North Carolina.

“Container and Fragrant Gardens” is derived from two previous works by Peter Loewer, a prolific garden author in North Carolina.

The plants in the container section are all listed as perennials, including small trees, though in our area, those in Zones 6 and up would be considered annuals. The fragrant part of the book includes annuals and perennials. They could be grown in containers, too.

“Best Perennials for Sun and Shade” is another combination of two books featuring two pages per plant—a nearly larger than life photo on one and growing information on the second. What I like is the little box for each plant that sums up growing zone, bloom time, light requirement, height and “interest”—leaf and flower description—in case you hadn’t noticed the full-page photo opposite.

“Best Roses, Herbs, and Edible Flowers” could conceivably have some of the same plants as the previous books. In addition to pages of luscious closeups, there is a chapter on harvesting and preserving herbs.

“Best Roses, Herbs, and Edible Flowers” could conceivably have some of the same plants as the previous books. In addition to pages of luscious closeups, there is a chapter on harvesting and preserving herbs.

“Attracting Birds and Butterflies” is a derivation of author Barbara Ellis’s previous work. It is supplemented with excerpts from books published by Bird Watcher’s Digest.

“Attracting Birds and Butterflies” is a derivation of author Barbara Ellis’s previous work. It is supplemented with excerpts from books published by Bird Watcher’s Digest.

In addition to plant profiles, there’s a page apiece for each butterfly and bird species that appreciates flower nectar. What I like is the critter profiles include a range map so you can concentrate on attracting the species you might see where you garden. However, the western birds profiled don’t include the seed eaters that also visit Cheyenne gardens.

For growing information for perennials—roses, herbs, flowers, shrubs, you would be better off consulting local information—don’t add lime to our soil as recommended in one of the books! And if you are growing our native perennials, don’t try to turn your soil into deep loam as suggested—our hardy prairie flowers don’t think much of luxury.

Old “Garden Gossip”

Old “Garden Gossip”

My favorite winter garden reading is much older garden books. I find them at used bookstores and the local Delta Kappa Gamma annual book sale.

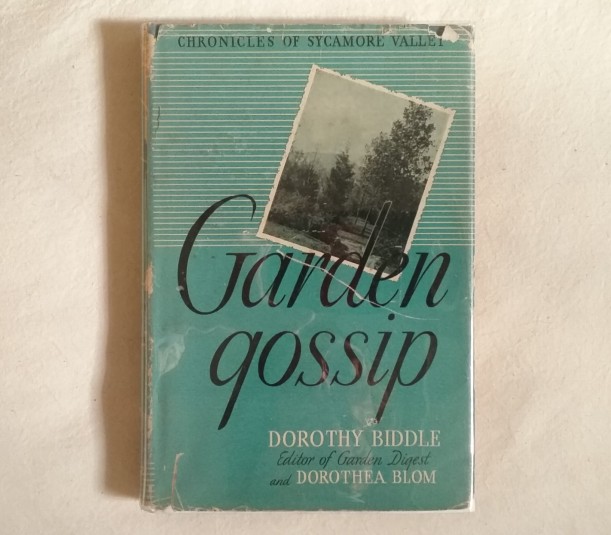

In Houston I found “Garden Gossip, Chronicles of Sycamore Valley” by Dorothy Biddle, editor of Garden Digest, and Dorothea Blom. It was published in 1936 with a price of $1. It was signed by the author as “Dorothy Biddle Johnson” in June of that year.

Informally, this column I write is known as “Garden Gossip” and the online archive is www.CheyenneGardenGossip.wordpress.com, so I couldn’t resist bringing the book home—for $20.

A small book, it has only a few plates of black and white photos inserted, but every chapter heading has a detailed ink sketch. And the chapters seem to be gossip, for instance “Color, Drama and Tomatoes, Mrs. L’s Garden.”

But the cover’s inside flap writeup suggests the people and gardens profiled may be serving an educational purpose, “Through the successes and mistakes of Sycamore Valley gardeners the reader receives a wealth of suggestions, many of which he will apply in his own garden.”

The mythical Sycamore Valley is probably based on Dorothy Biddle’s hometown of Pleasantville, New York, so I take the 85-year-old gardening advice with advisement. But the generalities still work.

For instance, Mr. and Mrs. B manage to make a lovely garden on a very limited budget. Dorothy writes, “Gardeners crave a little money to bury in the soil, but what happened in their garden happened almost entirely from labor and thought blended.” Now there’s a statement that can stand the test of time.

Dorothy Biddle was also Mrs. Walter Adams Johnson. Her co-author, Dorothea Blom, was her daughter. Dorothy founded the Blue Ribbon Flower Holder Company (one of her other books was “How to Arrange Flowers”) and when I checked a couple years ago, her granddaughter still owned the business. Dorothy died in 1974 at age 87, garnering an obituary in the New York Times, https://www.nytimes.com/1974/10/19/archives/dorothy-johnson-wrote-of-flowers.html.